Table 1 – General records of small-scale industrial businesses (1890-1930)

|

Documents |

Samples |

Total number of industrial businesses |

% |

Italian origin |

Italian origin % |

|

License permits |

2,328 |

446 |

19.15% |

202 |

45.29% |

|

Tax books – complete documentation |

6,598 |

1,222 |

18.52% |

701 |

57.36% |

|

Tax books – incomplete documentation |

4,150 |

647 |

15.59% |

346 |

53.47% |

|

Tax book–1899 |

2,145 |

360 |

16.78% |

207 |

57.5% |

|

Total |

15,221 |

2,675 |

17.57% |

1,456 |

54.42% |

Source: APHRP – License Permits (1891-1902); Yearbook of Trade of the State of São Paulo (1904) and Books of Taxes on Industry, Trade, and Occupations (1899-1930).

There were 15,221 records in all; 2,675 were of small industrial businesses, or 17.57% of the total. Of this amount, 54.42% had individuals of Italian origin as owners. Of the 1,452 records of people with Italian surnames, excluding trademarked and duplicate records, we obtained 752 records.[28] We had the names of those who were industrialists and could now check their humble origins. The documentation that could provide us with data about these people when they were still young was the Books of Records of Marriages, because they usually married early, soon after adolescence. With that, there was the possibility that many had declared the profession they had pursued in Italy. Of the 752 people named, 107 were married in Ribeirão Preto. Based on these marriage records, we determined the nationalities of the grooms, their professions, and the occupations of their godfathers and marriage witnesses. The results concerning the nationalities of the grooms are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 – Nationalities of the Grooms

|

Nationalities |

Grooms |

| Italian | 81 |

| Brazilian | 17 |

| Austrian | 06 |

| Spanish | 01 |

| Not declared | 02 |

| Total | 107 |

Source: Books of Records of Marriages of the First Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto (1890-1930).

Of the 17 grooms of Brazilian nationality, 10 were children of Italians (the first generation born in Brazil). The documentation does not identify the nationality of the other seven grooms’ parents, but their last names suggest the origin of their parents: Giacheto, Franzoti, Codognotto, Ferracini, Codogno, Casanova, Grandini.

The records of marriages contain the occupations of grooms and witnesses; on that basis, we establish some divisions in the research. So, we first selected grooms who are workers, whose witnesses or godfathers, with few exceptions, were also employed as workers. We classify workers as those who performed manual occupations, with low pay and low social prestige.[29] Frequently, people choose their godparents from among those closest to their social circle, so the profession of the godfather of a groom who is a worker can prove the modest origins of the godson. Secondly, we analyze groom workers whose godfathers performed activities in which they were not necessarily workers themselves or had a high-level profession – or one that provided social status to those who pursued it, aside from being well-paid.[30] Subsequently, we investigated the few records of grooms with high-level professions whose godfathers were workers. Finally, in the last installment of our sample, we analyzed the grooms and godfathers with high-level professions.

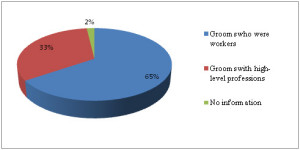

The empirical research revealed the data contained in Table 3. The Graph 1 provides us with the percentage of workers in the total sample of business owners. These data support our thesis about the humble origins of these industrialists.

Table 3 – The profession pursued by industrial business owners at the time of marriage

|

Classification |

Total of Grooms |

| Worker grooms with godfathers who are workers |

57 |

| Worker grooms with godfathers who hold high-level professions |

13 |

| Grooms with high-level professions whose godfathers are workers |

04 |

| Grooms and their godfathers who hold high-level professions |

31 |

| Total |

105* |

Source: Books of Records of Marriages of the First Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto (1890-1930).

Graph 1 – Percentage of groom workers and those with high-level professions

Source: Books of Records of Marriages of the First Civil Registry Office of Ribeirão Preto (1890-1930).

In the sample of 107 industrialists, 70 said they were employed as workers at the time of their marriages. Of these, many had godparents who were also employed as workers. Thus in Ribeirão Preto, those who had modest economic resources but some know-how could take advantage of investment opportunities offered by the city’s economy in order to advance their status from workers to businesspeople.

3.2. The foreign origin of the shoemaking business class in the city of Franca

In 1920 Franca had 44,308 inhabitants, only 6,193 of whom were immigrants – approximately 14% of the population. Of all foreigners, 2,889 were Italians and 2,281 were Spaniards.[31] Unlike Ribeirão Preto, these immigrants found major obstacles in their strategies of social mobility, as they did not have privileged access to land. By the time these immigrants arrived in the city, they found the city’s rural properties dominated by small units that were already occupied by Brazilians.[32] Moreover, foreigners were not the major source of the labor supply. They had to compete with national migrants, especially miners[33] – the city is close to the state of Minas Gerais – and they were attracted by the possibility of better jobs. Since immigrants had to compete for the best jobs, for many years they often, before settling in urban areas, worked as field hands or paid farmers on someone else’s land.

Another feature of Franca’s economy was that the coffee plantation did not represent a monoculture or a classic model of plantation economy[34] because the smallholdings, farms, and properties in the city had other types of crops or, especially, livestock. Even before the arrival of coffee to the city, livestock was the mainstay of this region’s economy. Franca was a trading post of the “Highway of Goiases” – responsible for commercially connecting the capital of the then-province of São Paulo and Goiás and Mato Grosso – and the mainstay of this Franca market was livestock, meat, and hides.[35] The leather market in town alongside the handicraft products made from leather (including harnesses, boots, sandals, and sheaths) increased the importance of livestock in the city. Along with the arrival of the coffee industry in the late nineteenth century, a booming sector was the leather industry, which, besides supplying a broader trade circuit (the drovers’ route, and later the cities linked by the Mogiana Railroad Company), created the conditions for the development of the shoemaking industry in this location.[36]

As with the embryonic process of industrialization that occurred in Ribeirão Preto (1890-1930), what was most distinctive about establishments arising from the shoemaking industry in Franca between 1900 and 1960 was their size. In a landmark study on this topic based on extensive documentation, Agnaldo de Sousa Barbosa empirically demonstrated that this sector very slowly veered away from the craft production stage. According to him, “[…] o grande capital esteve ausente da formação da indústria do calçado, somente se fazendo presente a partir dos anos 1960, quando o setor já se encontrava plenamente consolidado no município.”[37] These developments often arose from the efforts from simple shoemakers and their hand tools – given that the use of machines in these industries, to date, only complements manual skills, which are ultimately responsible for the final product.

Despite the obstacles encountered in Franca, immigrants and their descendants found in the leather and footwear industry a lever for social mobility. With that in mind, the ethnicity and social origins of these business owners are a relevant factor. Based on this, we surveyed all industrial and commercial establishments registered in Franca between 1900 and 1960. Since the nationality of people for the most part did not appear in the books of Records of Commercial Firms, at the Clerk of the General Register of Mortgages and Annexes of Franca, we adopted the same methodology used with the documentation of Ribeirão Preto. That is, we used the last name as a sorting element. In Franca, unlike in Ribeirão Preto, the Italians did not constitute an absolute majority, because this city had a strong Spanish and Portuguese presence. Distinguishing these two ethnic groups from the rest of the population by surname is somewhat difficult, since many Brazilians have Spanish or Portuguese last names (such as Garcia, Pereira, Oliveira, and Silva). Therefore, to avoid inaccurate results, we studied only people with Italian, Syrian, and Lebanese surnames.[38] These ethnic groups’ participation in the city’s economy provided us with a reasonable sample of the integration of immigrants into the society of Franca, especially in establishments that started the shoemaking cluster. Another point to be explained is that we classified all other ethnicities as “Other.” Starting with the 1940s, the nationality of each person was included in documentation, which facilitated our classification. However, when it came to Brazilians whose names we identified as Italian, Syrian, or Lebanese, we classified them in their nationality of origin.

In order to systematize this research, we created five types of activities to fit the many names of establishments present in the documentation. In Table 4, we list the five types of activities, as well as some sample of establishments.

Table 4 – Classification of industrial and commercial establishments in Franca

(1900-1960)

|

Type of activity |

Designation of the establishment |

| Rural activity | Farming development and agricultural development, among others. |

| Urban commerce | Haberdasheries, fabrics, grocery, pharmacy, butcher, stationery, and taverns, among others. |

| Other industries | Carpenters, metalworkers, processing of agricultural products, soap factories, and foundries, among others. |

| Leather-footwear | Tanneries, shoe factories, making of harnesses, and shoe makers, among others. |

| Provision of services | Transportation services, repair shops, guesthouses, and hotels, among others. |

Source: Records of Commercial Firms at the Clerk of the General Register of Mortgages and Annexes of Franca. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

Even though it was not the purpose of this type of record, some rural activities were included in the documentation. Although they are few in number, we present this data and preserve the computation of total enrollments. Based on the breakdown of establishments, we try to assess the participation of people of foreign origin in each type of activity, within ten-year periods. Table 5 presents the results. The three different shades of gray denote the level of immigrant participation in the type of activity throughout the period presented. Thus, light gray symbolizes that the participation of immigrants was below the number of nationals, medium gray that the number was equal or close to the number of nationals, and dark gray denotes that the number of immigrants was above the number of nationals.

Table 5 – Participation of immigrants and their descendants in Franca’s economy

(1900-1960)

|

1901-1910 |

|||||

|

Type of business activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 04 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 04 |

Urban commerce |

91 | 15 | 23 | 10 | 139 |

| Other industries | 03 | 05 | 00 | 00 | 08 |

| Leather-footwear | 16 | 03 | 00 | 00 | 19 |

| Provision of services | 00 | 01 | 00 | 00 | 01 |

| TOTAL | 114 | 24 | 23 | 08 | 171 |

|

1911-1920 |

|||||

|

Type of activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 00 | 01 | 00 | 00 | 01 |

Urban commerce |

66 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 108 |

| Other industries | 03 | 04 | 00 | 01 | 08 |

| Leather-footwear | 14 | 04 | 00 | 02 | 20 |

| Provision of services | 03 | 03 | 00 | 00 | 06 |

| TOTAL | 86 | 25 | 16 | 16 | 143 |

|

1921-1930 |

|||||

|

Type of activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 01 | 01 | 00 | 00 | 02 |

Urban commerce |

138 | 39 | 43 | 49 | 269 |

| Other industries | 41 | 22 | 06 | 07 | 76 |

| Leather-footwear | 31 | 17 | 00 | 04 | 52 |

| Provision of services | 08 | 10 | 00 | 00 | 18 |

TOTAL |

219 | 89 | 49 | 60 | 417 |

|

1931-1940 |

|||||

|

Type of activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

Urban commerce |

62 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 122 |

| Other industries | 18 | 11 | 02 | 04 | 35 |

| Leather-footwear | 09 | 10 | 01 | 00 | 20 |

| Provision of services | 01 | 02 | 00 | 01 | 04 |

TOTAL |

90 | 43 | 25 | 23 | 181 |

|

1941-1950 |

|||||

|

Type of activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 01 | 00 | 00 | 01 | 02 |

Urban commerce |

344 | 135 | 69 | 85 | 633 |

| Other industries | 42 | 53 | 17 | 05 | 117 |

| Leather-footwear | 48 | 51 | 02 | 16 | 117 |

| Provision of services | 40 | 20 | 07 | 06 | 73 |

TOTAL |

475 | 259 | 95 | 113 | 942 |

|

1951-1960 |

|||||

|

Type of activity |

Brazilian |

Italian |

Syrian or Lebanese |

Other |

Total |

| Rural activity | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

Urban commerce |

308 | 107 | 37 | 65 | 517 |

| Other industries | 25 | 22 | 01 | 02 | 50 |

| Leather-footwear | 26 | 17 | 00 | 08 | 51 |

| Provision of services | 53 | 36 | 01 | 09 | 99 |

TOTAL |

412 | 182 | 39 | 84 | 717 |

Source: Records of Commercial Firms at the Clerk of the General Register of Mortgages and Annexes of Franca. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

Although persons of foreign origin were prominent between 1901 and 1910, the number of both other industries, as well as provision of services, is very small. The representation of those of foreign origin in urban commerce, on the other hand, though lower than that of nationals, is significant. In the same period, the leather-footwear establishments were largely owned by nationals. In the subsequent decade, despite a variation in numbers, the situation remained very similar; as for the leather-footwear industry, it showed an increase in the number of foreigners. In the 1920s, there were considerable changes, since in urban commerce the number of nationals compared to foreigners was very similar. Significantly, there was a large increase in the number of leather-footwear establishments, as well as in the participation of immigrants in this business. By the 1930s, the records indicated that there were already more businesses owned by foreigners than by nationals. In the shoemaking industry, although there was a drop in the number of establishments registered, they surpassed the number of nationals. In the following decade, the situation was the same, but there were more leather-footwear establishments, and foreigners far exceeded the number of nationals. In the last decade of the study, there was an economic slowdown in all types of activities, and participation of people of immigrant origin was below or close to that of nationals.

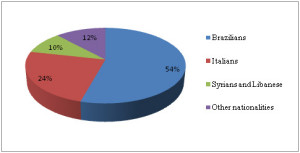

With respect to total percentages, we have prepared Graph 2 regarding the ethnic origin of the Franca business community (1900-1960).

Graph 2 – Ethnic origin of the business community of Franca

Source: Records of Commercial Firms at the Clerk of the General Register of Mortgages and Annexes of Franca. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

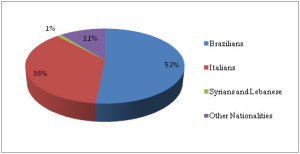

Regarding the ethnic distribution of the shoemaking-business owners, out of the 279 establishments operating during the period of our study, 144 belonged to Brazilians, 102 to persons of Italian origin, three to Syrians or Lebanese, and 30 to individuals of other nationalities. Graph 3 provides the breakdown of this group by ethnic origin.

Graph 3 – Ethnic origin of the footwear business community in Franca (1900-1960)

Source: Records of Commercial Firms at the Clerk of the General Register of Mortgages and Annexes of Franca. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

The next stage of the research was to find out how many of these people had humble origins. The documentation used was gathered from the Registry of Marriages, responsible for providing information on the occupations of all newlyweds married in Franca (1906-1960). We present this data in Table 6.

Table 6 – Origins and Professions of Grooms Married in Franca (1906-1960)

|

Employees in commerce/trade |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

05 |

25 |

33 |

78 |

130 |

135 |

| Immigrants |

01 |

03 |

04 |

03 |

07 |

01 |

| Descendants |

00 |

04 |

10 |

37 |

63 |

47 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

06 |

32 |

47 |

118 |

200 |

183 |

|

Employees in industry |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

06 |

29 |

82 |

65 |

105 |

402 |

| Immigrants |

02 |

32 |

47 |

07 |

03 |

01 |

| Descendants |

00 |

08 |

50 |

18 |

30 |

100 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

01 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

08 |

69 |

179 |

90 |

139 |

503 |

|

Employees in the fields/countryside |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

532 |

667 |

834 |

577 |

537 |

601 |

| Immigrants |

172 |

230 |

192 |

64 |

18 |

06 |

| Descendants |

10 |

129 |

205 |

154 |

105 |

87 |

| Not declared |

02 |

00 |

01 |

03 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

716 |

1026 |

1232 |

798 |

660 |

694 |

|

Freelance professionals |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

09 |

27 |

31 |

28 |

41 |

64 |

| Immigrants |

00 |

02 |

01 |

01 |

00 |

04 |

| Descendants |

00 |

02 |

05 |

08 |

17 |

15 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

09 |

31 |

37 |

37 |

58 |

83 |

|

Service providers |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

52 |

148 |

207 |

269 |

416 |

784 |

| Immigrants |

31 |

67 |

41 |

23 |

18 |

14 |

| Descendants |

10 |

53 |

111 |

145 |

213 |

282 |

| Not declared |

00 |

02 |

00 |

00 |

03 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

93 |

270 |

359 |

437 |

650 |

1080 |

|

Commercial businessmen |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

11 |

49 |

41 |

40 |

33 |

85 |

| Immigrants |

10 |

27 |

51 |

35 |

10 |

16 |

| Descendants |

01 |

17 |

22 |

41 |

35 |

70 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

22 |

93 |

114 |

116 |

78 |

171 |

|

Industrialists |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

03 |

05 |

09 |

02 |

06 |

17 |

| Immigrants |

02 |

01 |

02 |

02 |

01 |

01 |

| Descendants |

00 |

00 |

02 |

03 |

10 |

19 |

| TOTAL |

05 |

06 |

13 |

07 |

17 |

37 |

|

Landowners |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

04 |

06 |

03 |

09 |

28 |

93 |

| Immigrants |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

01 |

00 |

| Descendants |

00 |

00 |

00 |

02 |

02 |

01 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

04 |

06 |

03 |

11 |

31 |

94 |

|

Leather-footwear sector |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

15 |

28 |

32 |

54 |

129 |

139 |

| Immigrants |

05 |

04 |

03 |

02 |

02 |

00 |

| Descendants |

01 |

07 |

21 |

37 |

82 |

58 |

| Not declared |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

21 |

39 |

56 |

93 |

213 |

197 |

|

Did not declare a profession |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| Brazilians |

54 |

31 |

09 |

09 |

11 |

11 |

| Immigrants |

20 |

08 |

02 |

00 |

02 |

00 |

| Descendants |

03 |

07 |

06 |

06 |

04 |

06 |

| Not declared |

00 |

02 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| TOTAL |

77 |

48 |

17 |

15 |

17 |

17 |

|

TOTAL NUMBER OF MARRIAGES |

||||||

| 1906-1910 | 1911-1920 | 1921-1930 | 1931-1940 | 1941-1950 | 1951-1960 | |

| TOTAL |

961 |

1620 |

2057 |

1722 |

2063 |

3059 |

Source: Registers of banns of marriages performed in Franca between 1906 and 1960. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

We used the same grayscale to rate the number of people of foreign origin in relation to nationals, and the darker the shade, the more foreigners. In only a few cases do the numbers of immigrants and their descendants match or exceed those of Brazilians. Immigrants and descendants equaled or exceeded Brazilians, for some decades, among commercial businessmen. And despite the small number of self-proclaimed industrialist grooms, during the last three decades of our study, the number of foreigners and descendants surpassed those of Brazilians – as our thesis anticipated. With respect to employees in industries, only twice between 1910 and 1920 did the number of foreigners exceed those of Brazilians. Among the employees in the fields, immigrants and descendants were always outnumbered.

Another observation about the rural population is necessary: there were few married owners of rural properties in the city. The reason may be that rural Franca properties tended to be medium-sized and small. When these medium and small farmers disclosed their profession to the Marriage Registrar, they may have preferred to call themselves farm workers. Therefore, there may have been many of these included in the study as employees in the fields. Those who said they were landowners or farmers were, perhaps among other things, large landowners in the strictest sense of the term.

There were always a large number of immigrant grooms along with descendant grooms who worked in the leather-footwear industry sector, despite being outnumbered by the Brazilians throughout this period. In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s they made up approximately 40% of all the grooms in this economic sector.

Of the owners of the 279 establishments surveyed in the first phase of the study, 144 were married in Franca. Of these, 72 were born in Brazil to Brazilian parents; 62 were born in Brazil of foreign parents, and 10 were born abroad. That is, half of the sample was of foreign origin. Table 7 contains the occupations performed by these businessmen at the time of their marriage.

Table 7 – Professional Occupation Performed at the Time of Marriage

|

Performed business activities |

Total |

| Tailor |

01 |

| Artist |

06 |

| Barber |

02 |

| Chauffeur |

01 |

| Store owner |

06 |

| Retail |

04 |

| Cutter |

01 |

| Shoe cutter |

01 |

| Store employee |

05 |

| Employee of the Franca Electric Company |

01 |

| Industrial worker |

01 |

| Farmer |

07 |

| Carpenter |

02 |

| Mechanic |

02 |

Laborer |

15 |

| Mason |

02 |

| Teacher |

01 |

| Shoemaker |

35 |

| Saddle maker |

04 |

| Traveler |

01 |

Not declared |

06 |

| Lawyer |

01 |

| Banker |

01 |

| Dentist |

01 |

| Merchant |

08 |

| Accountant |

04 |

| Pharmacist |

01 |

| Bookkeeper |

03 |

| Industrialist |

15 |

Performed business activities |

Total |

| Dealer/salesperson |

04 |

Owner |

01 |

| Chemist |

01 |

TOTAL |

144 |

Source: Registers of banns of marriages performed in Franca between 1906 and 1960. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

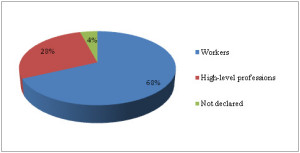

Based on these professions, we repeat the classifications previously used, namely those of worker [39] and high-level profession.[40] Thus Graph 4 shows the percentages for both categories.

Prominent among the occupations declared at the time of marriage were those related to the workers’ own activities, that is, handicrafts, which were poorly paid and without much social prestige. And, in smaller numbers, those with a high-level profession, with higher social status.

Graph 4 – Professional origin of the businessmen in the leather-footwear industry at the time of marriage (1900-1960)

Source: Registers of banns of marriages performed in Franca between 1906 and 1960. Municipal Historical Archive of Franca (AHMUF).

Besides this observation, the fact that the shoemaking industry demanded more craftsmanship than technology and machinery at that embryonic stage, investment in this activity was not an obstacle to immigrants or their poor descendants. The important thing to start the business was the know-how – brought over from Europe, Syria, or Lebanon, or learned in Brazil, perhaps with a cobbler.

Final Considerations

The creation of the manufacturing business class in the state of São Paulo took on complex traits and even characteristics that belie the consensus created by the academic literature, which is responsible for directly associating the figure of the industrialist with that of the rich foreigner or the coffee grower-investor and associating poverty with the immigrant worker. However, during the process of industrialization in Ribeirão Preto and Franca, the wealthy immigrant or the coffee grower were absent. Those who prevailed arrived at the right place at the right time and made full use of the opportunities created by societies undergoing change amid the dynamics created by the coffee economy.

The small manufacturing enterprises of these two cities represented the opposite of the medium and large industries in the city of São Paulo during the same period. Therefore, when discussing industrialization and immigration in the state of São Paulo, the simple actions of foreign workers and their descendants, holders of a certain know-how, can help tell an important story about the creation of the business community in Brazil.

References

Adriana Adriana Capretz Borges Silva, Expansão urbana e formação dos territórios de pobreza em Ribeirão Preto: os bairros surgidos a partir do Núcleo Colonial Antonio Prado, master´s thesis, São Carlos, Ufscar, 2008.

Agnaldo de Sousa Barbosa, Empresariado fabril e desenvolvimento econômico: empreendedores, ideologia e capital na indústria do calçado (Franca, 1920-1990), São Paulo, Hucitec/FAPESP, 2006.

Caio Prado Júnior, História econômica do Brasil, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1976.

Carlos A. P. Bacellar, Na estrada do anhanguera: uma visão regional da história paulista, São Paulo, Humanitas, FFLCH/USP, 1999.

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Empresário industrial e o desenvolvimento econômico no Brasil, São Paulo, Difusão Européia do Livro, 1964.

Herbert S. Klein, Migração internacional na história das Américas. In Boris Fausto, Fazer a América, São Paulo, Ed. Usp, 2000.

João Manuel Cardoso Mello, O capitalismo tardio, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1984.

José de Souza Martins, O cativeiro da terra, São Paulo, Ciências Humanas Ltda., 1979.

Luiz Carlos Bresser Pereira, Empresários e administradores no Brasil, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1974.

Rosana Aparecida Cintra, Italianos em Ribeirão Preto: vinda e vida de imigrante (1890-1900), master´s thesis, Franca, UNESP, 2001.

Samuel L. Baily, The adjustment of Italian immigrants in Buenos Aires and New York (1870-1914). In American Historical Review 88, nº. 2 (April 1983): 281-305.

Sérgio Silva, Expansão cafeeira e origens da indústria no Brasil, São Paulo, Alfa-Omega, 1995.

Warren Dean, A industrialização de São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Bertrand Brasil, 1991.

Wilson Cano, Raízes da concentração social em São Paulo, São Paulo, Unicamp/IE, 1998.

* Postdoctoral Fellow at FAPESP – the São Paulo Research Foundation and a researcher linked to the Department of Education, Social Sciences and Public Policy of UNESP – São Paulo State University and to LabDES – Laboratory of Development and Sustainability Studies.

Address: Rua João Batista de Barros, 592 – Jardim Nova Guaxupé – CEP. 37800-000 – Guaxupé/MG/Brazil.

Phone: 55-35-3552-6031 – Cell phone: 55-35-8882-6031.

Email: maranbrand@yahoo.com.br

[1] Caio Prado Júnior, História econômica do Brasil, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1976.

[2] Ibid., pp. 265.

[3] Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Empresário industrial e o desenvolvimento econômico no Brasil, São Paulo, Difusão Européia do Livro, 1964.

[4] Ibid., pp. 82.

[5] Luiz Carlos Bresser Pereira, Empresários e administradores no Brasil, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1974.

[6] The survey results reported that 21.5% belonged to the upper middle class (the main feature of which is the higher education and the independent profession of the father; the family is generally rich, occasionally making ends meet). About 30% belonged to the middle class (consisting of families who could make ends meet, with parents with secondary education, in general, exercising professions such as mid-level civil servant, businessman, industrialist, or mid-level farmer). And 20% belonged to the lower middle class (consisting of poor families, or at most those able to make ends meet, where the father usually completed primary education or, at most, high school, and the father’s profession was commerce, banking, retail merchant, industrialist, or farmer). L. C. B. Pereira, Empresários, cit, pp.,110.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., pp. 124.

[9] Warren Dean, A industrialização de São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Bertrand Brasil, 1991.

[10] Ibid., pp. 26.

[11] “[…] almost all Brazilian businessmen came from the rural elite. Around 1930, there was not one single manufacturer born in Brazil originating from the lower or middle classes, and very few came later.” Ibid. pp. 54.

[12] “[…] had little chance of rising above the lower class; at most he could reach the level of retail sales or repair shops.” Ibid. pp. 59.

[13] Sérgio Silva, Expansão cafeeira e origens da indústria no Brasil, São Paulo, Alfa-Omega, 1995.

[14] “[…] the majority of the Brazilian industrial bourgeoisie arrived as immigrants to Brazil in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century and worked as importers.” Ibid., pp. 90.

[15] S. Silva, Expansão, cit., pp. 91.

[16] José de Souza Martins, O cativeiro da terra, São Paulo, Ciências Humanas Ltda., 1979.

[17] Ibid., pp. 148.

[18] João Manuel Cardoso de Mello, for instance, said, “[…] a burguesia cafeeira não teria podido deixar de ser a matriz social da burguesia industrial, porque era a única classe dotada de capacidade de acumulação suficiente para promover o surgimento da grande indústria” – “[…] the coffee-growing bourgeoisie could not help but be the social matrix of the industrial bourgeoisie, because it was the only class with enough capacity of accumulation to promote the emergence of big industry.” In João Manuel Cardoso Mello, O capitalismo tardio, São Paulo, Brasiliense, 1984, pp. 143. Wilson Cano also contended that the industry did not emerge in Brazil through a process of transformation from craft production and manufacturing to industrial production. Wilson Cano, Raízes da concentração social em São Paulo, São Paulo, Unicamp/IE, 1998, pp. 224-225.

[19] Herbert S. Klein, Migração internacional na história das Américas. In Boris Fausto, Fazer a América, São Paulo, Ed. Usp, 2000, pp. 28-29.

[20] Ibid., pp. 29.

[21] “[…] the Italians in these two nations rapidly entered the newly created middle class, and already in their second generation, many of them had already achieved a higher status than their own parents had.” Ibid.

[22] Samuel L. Baily, The adjustment of Italian immigrants in Buenos Aires and New York (1870-1914). In American Historical Review 88, no. 2 (April 1983): 281-305.

[23] Ibid., pp. 285.

[24] S. L. Baily, The adjustment, cit.

[25] Carlos A. P. Bacellar, Na estrada do anhanguera: uma visão regional da história paulista, São Paulo, Humanitas, FFLCH/USP, 1999.

[26] Report (1902) presented to the City Council at Ribeirão Preto by the City Mayor Dr. Manoel Aureliano de Gumão, in the Session of January 10, 1903. São Paulo: Duprat & Compp. 1903. APHRP – Public and Historical Archive of Ribeirão Preto.

[27] Rosana Aparecida Cintra, Italianos em Ribeirão Preto: vinda e vida de imigrante (1890-1900), master´s thesis, Franca, UNESP, 2001, pp.72-73.

[28] By analogy, this ratio also occurs in other establishments and for other ethnic groups found in the documentation.

[29] Among the professions were tailor, carpenter, wagoner, settler, employee of Mogiana Railroad Co., trade employee, carver, farrier, blacksmith, tinker, farmer, carpenter, mechanic, laborer, baker, bricklayer, planter, shoemaker, dyer, and rural worker.

[30] Among others were trader, builder, industrialist, doctor, merchant, and owner.

* Two grooms did not declare the profession they pursued at the time of marriage.

[31] Agnaldo de Sousa Barbosa, Empresariado fabril e desenvolvimento econômico: empreendedores, ideologia e capital na indústria do calçado (Franca, 1920-1990), São Paulo, Hucitec/FAPESP, 2006, pp. 42.

[32] Ibid., pp. 47-50.

[33] People born in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

[34] Unlike Ribeirão Preto, which was surrounded by large estates with land-rock–the few lands that were unwanted by farmers were used for the Antonio Prado Colonial Center – the city of Franca was surrounded by an archipelago of small and medium properties. A. S. Barbosa, Empresariado, cit.

[35] Ibid., pp. 39.

[36] Ibid., pp. 39-41.

[37] “[…] big capital was absent from the creation of the shoemaking industry, only appearing from the 1960s onwards, when the industry was already fully consolidated in the county.” A. S. Barbosa, Empresários, cit., pp. 66.

[38] It is noteworthy that the “Brazilian” immigrants also include many Spanish and Portuguese immigrants.

[39] Tailor, artist, barber, chauffeur, store owner, retailer, cutter, shoe cutter, store employee, employee of the Franca Electricity Company, industrial worker, farmer, carpenter, mechanic, laborer, mason, teacher, shoemaker, saddle maker, traveler.

[40] Lawyer, banker, dentist, merchant, accountant, pharmacist, bookkeeper, industrialist, dealer/salesperson.